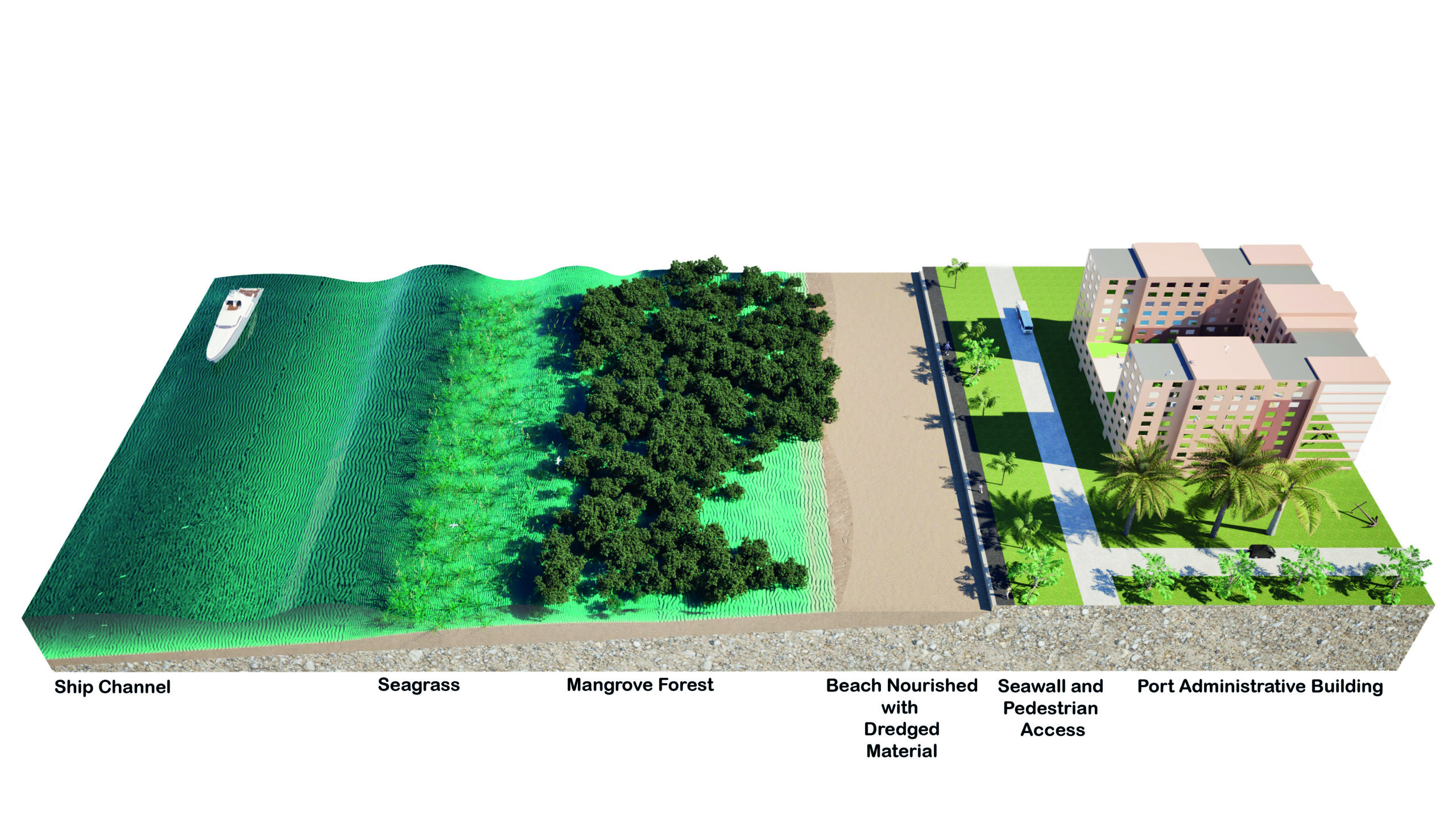

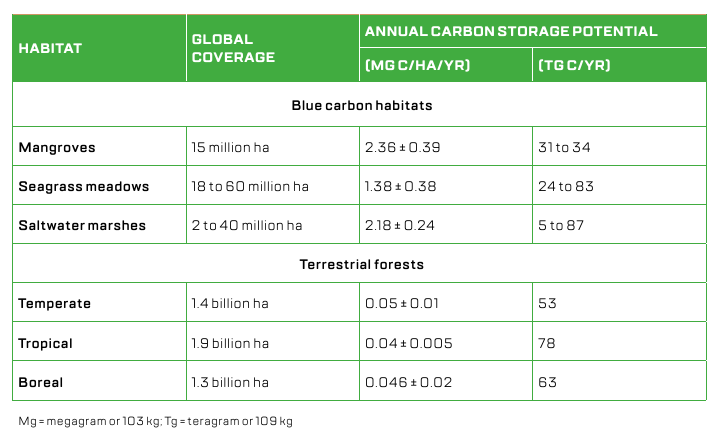

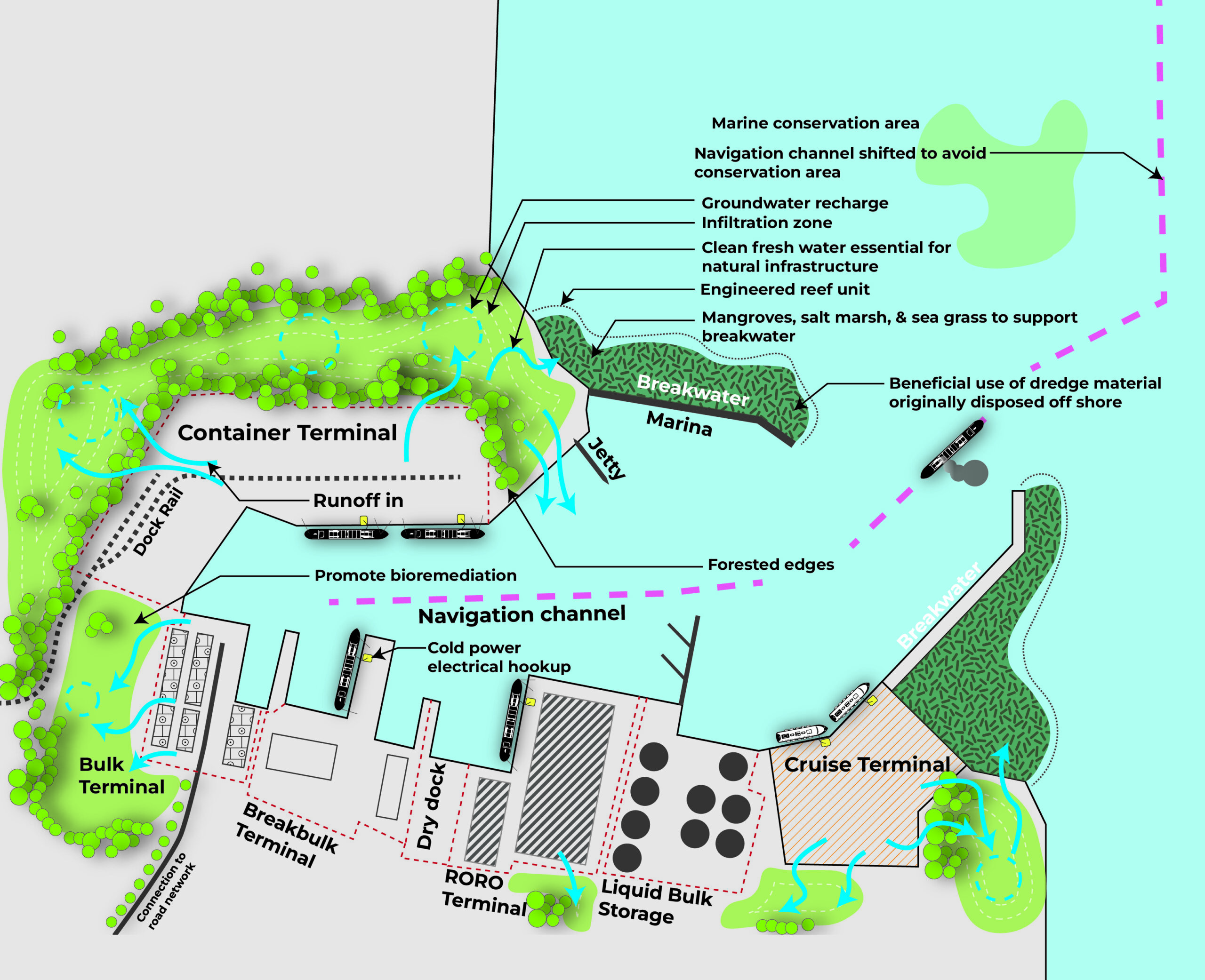

Ports and navigable waterways are pivotal to global trade but often are situated in and around marine coastal habitats, such as maritime forests, salt marshes and seagrasses – collectively known as blue carbon ecosystems. Blue carbon ecosystems (BCE) can sequester carbon at rates orders of magnitude greater than terrestrial ecosystems and are key components of the carbon mass balance in coastal environments, playing a vital role in long-term carbon management (McCleod et al., 2011). Protecting, restoring and managing BCE can help reduce the risks and impacts of a changing environment. These habitats also serve as natural infrastructure, reducing flood risk and associated vulnerabilities while providing multiple co-benefits through habitat enhancement including food provision, livelihoods and cultural services (Friess et al., 2024).

The World Association for Waterborne Transport Infrastructure (PIANC) recognises how effective management of coastal ecosystems is relevant to port, harbour and waterway assets and operations. Coastal and estuarine flood protection, beneficial use of dredged materials and the development of sustainable infrastructure are examples of the interface where navigation interests and opportunities for effective BCE management coincide. For these reasons, PIANC launched a Working Group on blue carbon whose objective is to define blue carbon and describe its relevance to waterborne transport infrastructure (W TI).

This article explains how navigational infrastructural elements relate to and affect blue carbon, and how holistic sediment management can support BCE management and improvement, leading to more resilient ecosystems. The decision- making process on how best to conserve and promote BCE, particularly at the intersection of WTI development and nature, is motivated by a range of experts and project influencers, including:

- Port authorities, navigation and river authorities and commissions, and terminal operators.

- Regulators, government agencies and elected officials.

- Project designers, contractors, ecologists, civil engineers, planners and landscape architects.

- Environmental stakeholders, NGOs, public

interest groups and other waterway users.

Background

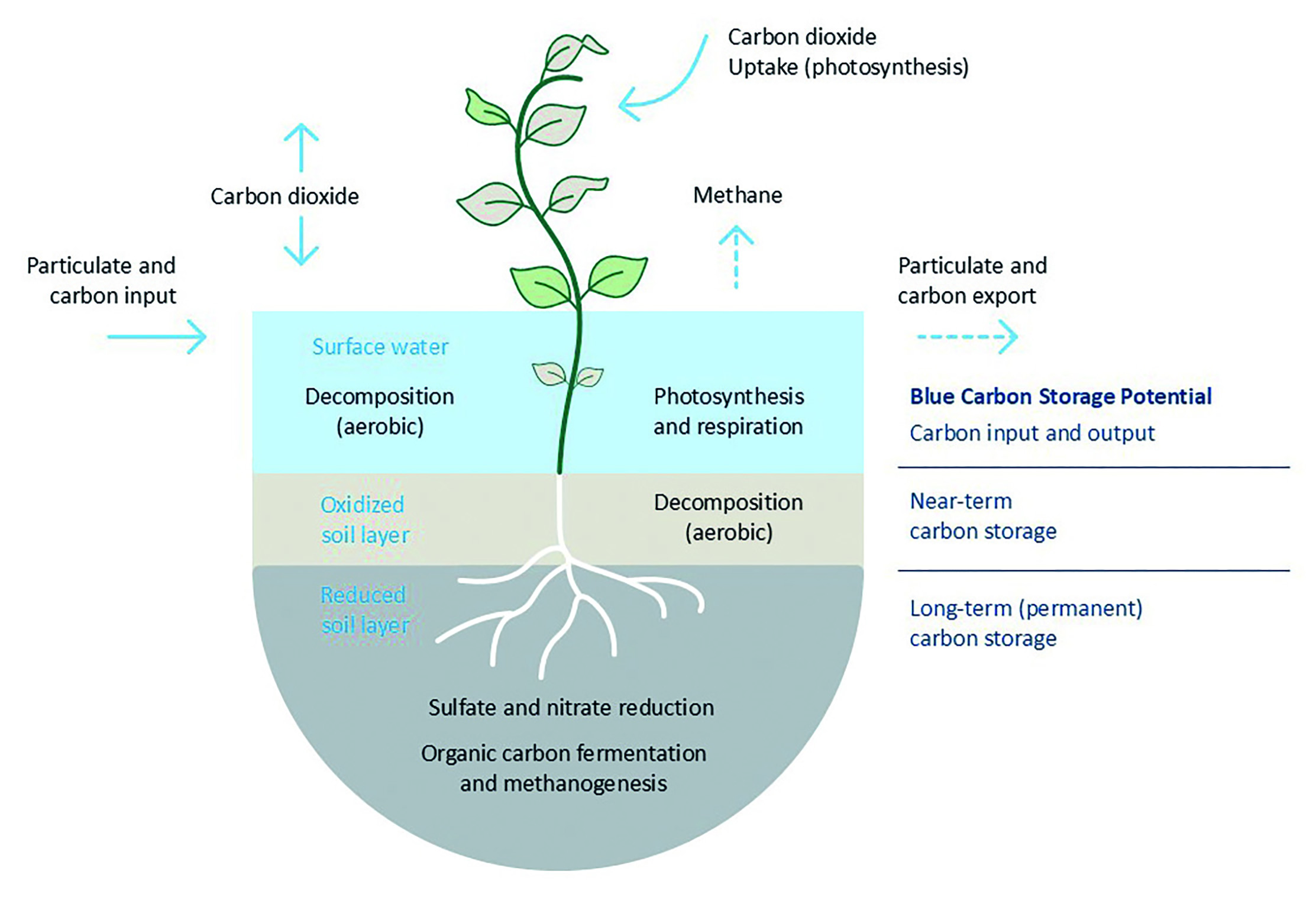

Sediment is a crucial part of aquatic ecosystems, forming the foundation for natural habitats and playing a vital role in sequestering and storing carbon. Blue carbon ecosystems absorb carbon through natural processes, such as sedimentation of organic- rich particles, photosynthesis, plant growth and decay, the partial decomposition of organic matter and the accumulation and burial of plant detritus (Figure 1). Short term carbon storage happens continuously at the sediment surface, while buried sediment and organic material contribute to long-term (permanent) carbon storage if left undisturbed. Estimates indicate that some mangrove forests and coastal wetlands are thousands of years old (Friess et al., 2019; Mangrove Action Project, 2016), representing long-term carbon storage and making them essential to the carbon mass balance in aquatic environments (Kristensen et al., 2025).